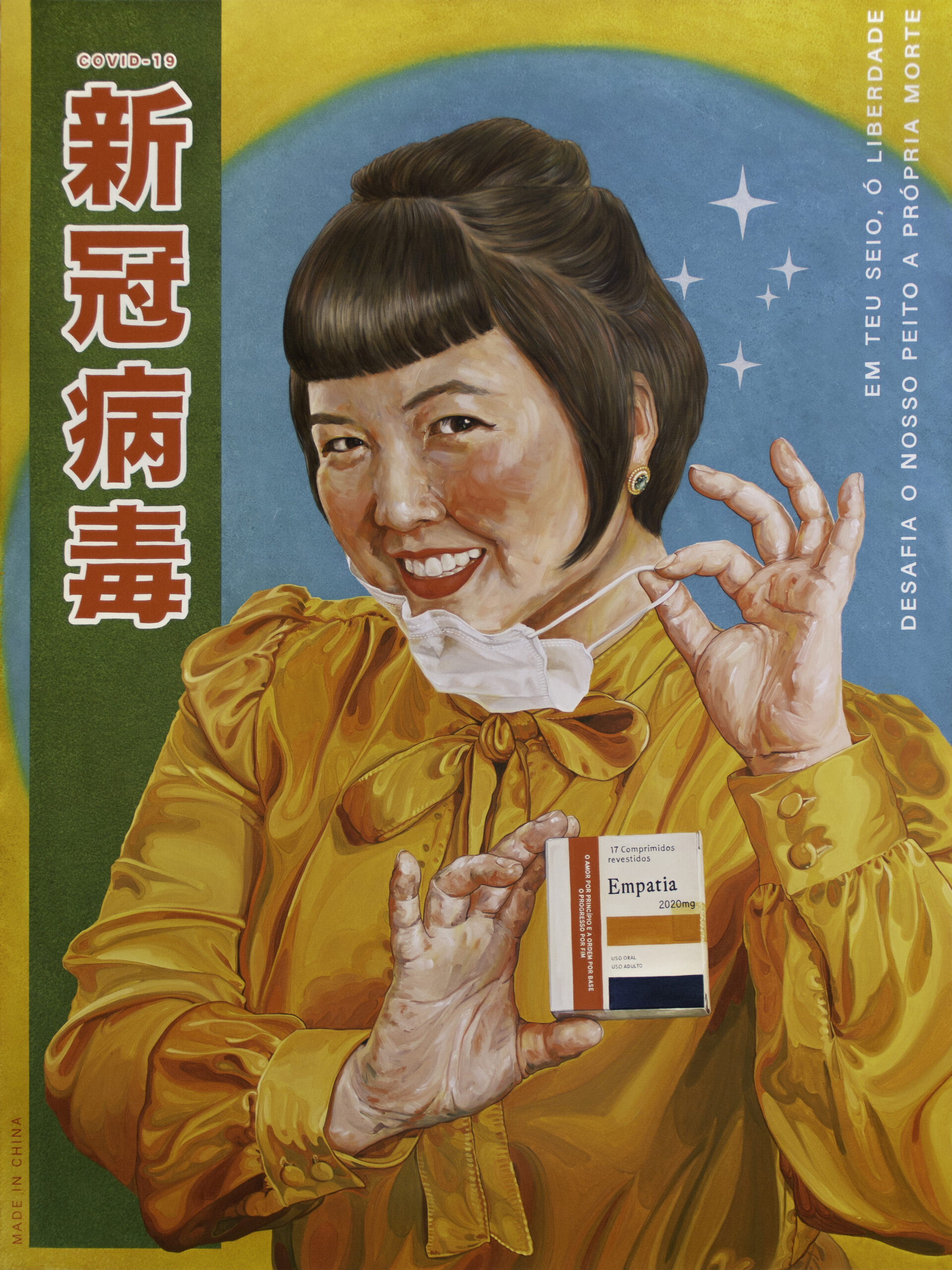

Marjô Mizumoto

Marjô Mizumoto (São Paulo, Brazil, 1988) is a Brazilian artist of Japanese descent with a keen interest in painting. Her works depict a world full of everyday family scenes and intimate moments, interspersed with the fantastic and the surreal. In the interview, the artist reveals how her experience as a mother and the influence of the people around her sparked her fascination with everyday life and her desire to interpret it on canvas. Each brushstroke is an expression of her emotional connection with a scene and guides viewers to a place of nostalgia. Check out the interview:

Marjô, I’d like to start by asking you to introduce yourself in any way you see fit, with information you consider relevant, especially for an audience that may not yet be familiar with your artistic practice.

I’m Marjô Mizumoto. I’m a mum, a wife, and an artist. I come from a whole family of doctors – I’m kind of the black sheep (laughs). I was born in Brazil, and all my ancestry is Japanese. I studied fine arts at FAAP and did a postgraduate course in art history, but I didn’t finish it. I got as far as the end, but I became pregnant and ended up putting off finishing the course until later. As a child, I studied at the Rudolf Steiner Waldorf School and, because of the school, I was always generally involved in the world of art. This contact has always been present. During university, I ended up assisting some artists, and this work led me to painting. I didn’t think I was going to be a painter but by the end of university it was the only thing I could see myself doing. Since then, I’ve followed the path of painting.

Your work manifests itself in painting, but there is a previous process of manipulating the digital image, as well as the stage of remembering and sharing your family context that then results in a painting. How do you see all these processes? How does the issue of memory work, which I believe is very important to you, and how did you achieve this resolution in the painting?

I think my preference for painting is due to my interests and skills. I’ve always been very interested in recording moments, whether with a camera or a mobile phone. At the same time, I was never good at it. At university, I began to explore the world of video and woodcuts, which sparked my interest in image-making. I consider my photography and filmmaking to be pretty average, but I feel that when I express my thoughts through painting, I can better translate what’s in my head. My interest in painting came about by chance, when I saw a scene that I couldn’t capture. I saw a woman looking up at the overcast sky, pulling out an umbrella with an anguished expression and that scene struck me. I remember driving past and thinking: “Wow, I wish I’d recorded that”, but I didn’t manage to. That’s when I started thinking of ways to translate that scene. I started photographing myself and trying to paint – not very well – in an attempt to capture that scene. But when I did that first painting in that way, I liked how I was able to create a world that didn’t exist in theory, making an assemblage of a composition of ideas and translating that into a plan. Recreating this on video for me was much more complex, as I would need someone to film and direct the scene, among other things. During university, I never considered filming as a path to follow. I always liked to work things out for myself. When I started manipulating images in Photoshop, creating a unique universe, I liked the result of the composition. However, editing my photos in Photoshop wasn’t something I considered a work of art. For me, it was a means to an end. In painting, I was seduced by the brushstroke and by color, by the possibility of transforming everything into a place, and then I found my place. Printmaking didn’t produce the amount of color I wanted, photography didn’t allow me to do this independently. Painting, on the other hand, gives me all this, and it’s in painting that I’m able to resolve these issues.

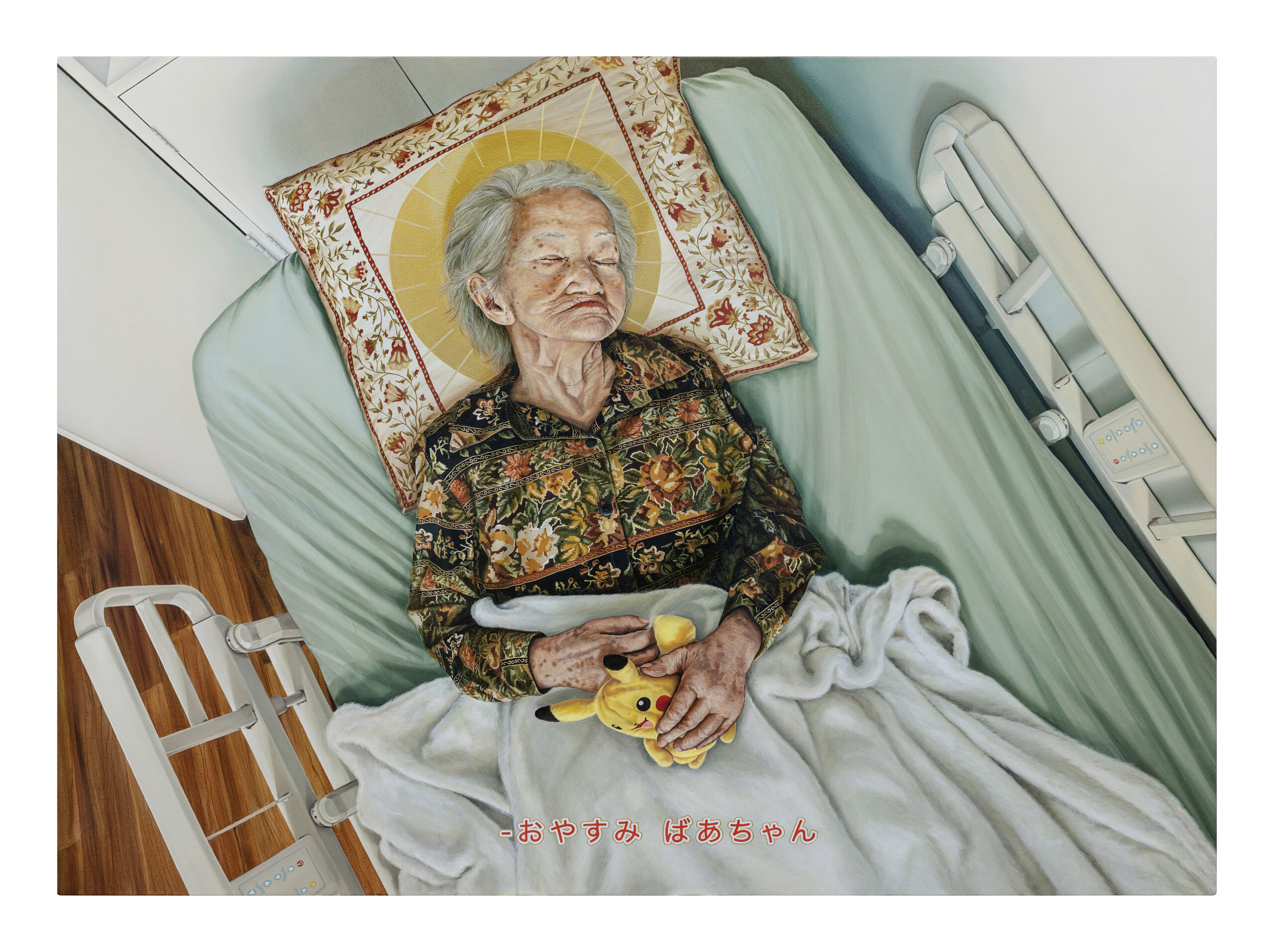

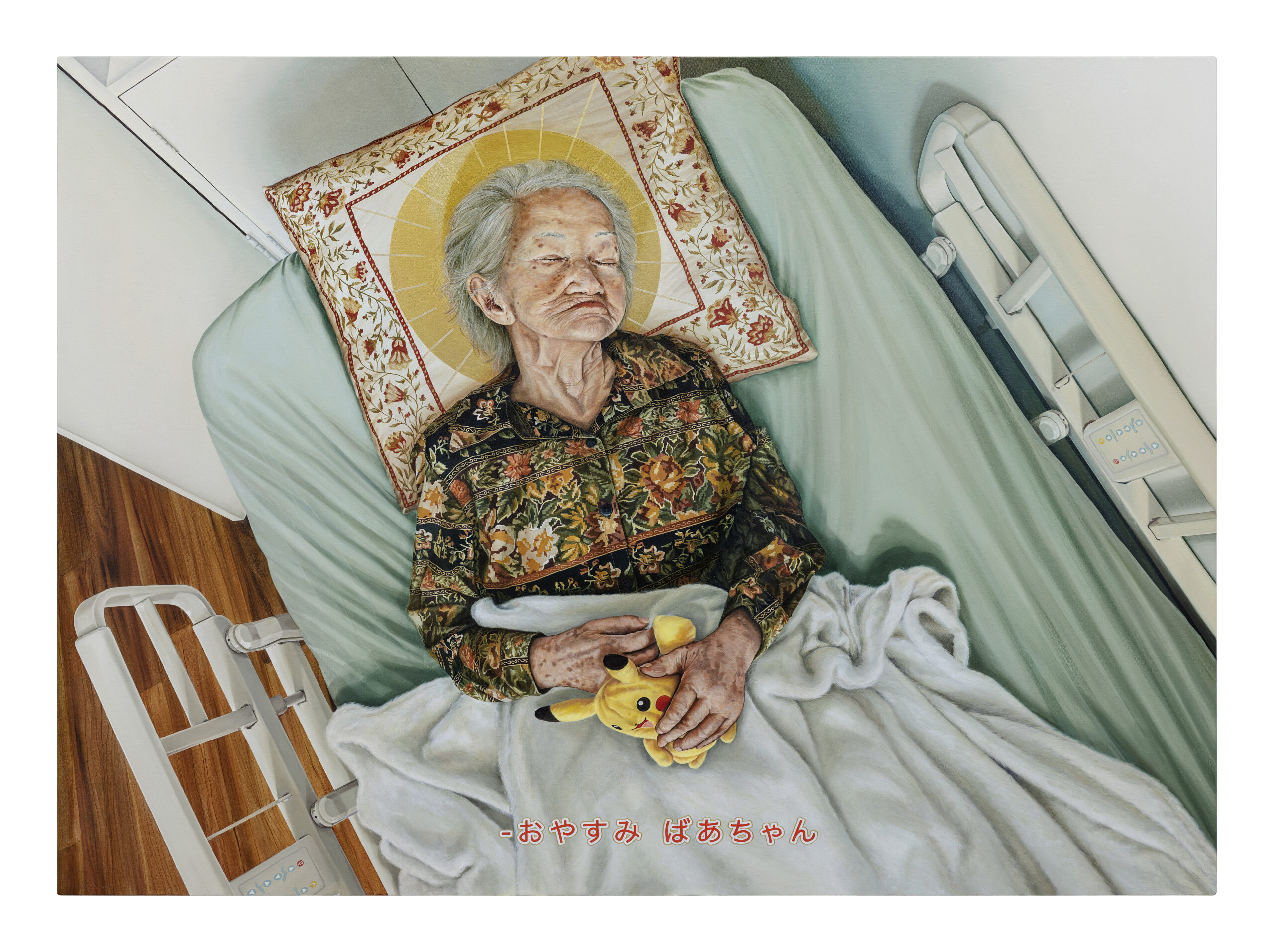

*Good night Grandma (Tiseko Yamaguchi), 2021-2022

It’s curious to think that painting can sometimes frighten the artist. This is often because of the history of art and the great masters who came before. But it’s interesting to see how you manage to appropriate media without feeling intimidated. On the contrary, you use all this history to bring ideas that arise from your research and your experiences in the field of painting.

Painting has never intimidated me, unlike other techniques. Maybe it’s because I started painting very freely, doing everything by hand and applying thick strokes with very hard brushes. If I was laying down large masses of paint and overlapping layer after layer, and everything was fine. Painting gave me a bit of the “Giacometti angst” of not getting it today, but tomorrow I’ll paint again, and again. If I know I haven’t solved it today, tomorrow I’ll look at the problem and face it. For me, painting has always been this challenge of me looking at it, it looking at me and saying: “How are we going to get along?” I don’t stop until it works. However, it’s not something that works first time round. For me, a painting always has to have at least three layers – it’s never just one – until I look at it and think it’s worked. Painting allows me to do that, to always go back and add more layers. In comparison, I find drawing much more intimidating. For me, drawing comes down to a line, sometimes a very simple one. It’s a synthesis of the image, while painting always offers me the chance to answer back.

In your work, I come to understand that the ideology of the image, that magical charm of the moment, is very present. This conversation with painting expresses this ideal moment better than a photograph, or even a video.

Transforming an image into a photo or video, so that everything looks so realistic that we question the veracity of the scene, is quite a complex process. After all, we’re used to seeing the world through our own eyes, and photography is just a representation of that. If something doesn’t look right, we notice it immediately. Painting, on the other hand, doesn’t exist until it exists. Everything I turn into a painting from photographs has the same language as the hand that is painting. When I choose photographs to put together in a design, I prepare everything in Photoshop before painting. It’s like putting together a scene from a film or theatre stage. I adjust and tweak the characters and the scenery, detail by detail, until the design is just right. If I showed you my design, you’d see that it was a collage, but when it’s done as a painting, I manage to bring everything into a single universe.

Yes, through the hand we have access to your universe. Nothing is more structured than painting, which carries with it a weight of reality. When we think of painting in the 14th and 15th centuries, which was the only form of artistic expression at the time, I like to imagine Napoleon asking to be portrayed as if he were two meters tall. It’s a construction, because when you see paintings of Napoleon, you could never guess his true height. It’s fascinating to reflect on these constructions because they were always intentional. It’s like having access to his world, his universe, because it’s by a hand that these paintings are created.

If Michelangelo or Da Vinci had access to the technologies we have today to create an image, they would go crazy (laughs). What they already did back then with a model posing and constructing in a more handmade way is impressive, so imagine that with today’s possibilities.

A pintura sempre surge desse lugar de criar algo. No final das contas, todo artista tem exatamente as mesmas coisas: tinta e pincel. Agora, o que aquele artista vai transformar com aquela tinta, como ele vai depositá-la, o que ele vai criar com isso, é o que está ali na cabeça dele.

(Translation: Painting always comes from that place of creating something. At the end of the day, every artist has exactly the same things: paint and a brush. Now, what that artist is going to transform with that paint, how he’s going to place it, what he’s going to create with it, is what’s in his head)

When thinking about your images, I can see that you use many scenes from your family’s daily life, which is very interesting. We can identify the era of each painting just by the age of the children. What inspired you to share these very personal moments and incorporate them into your paintings, which are the result of a longer process and are usually focused on the viewer?

I’ve always been very true to what really interested me, in my paintings. When I choose an image, it’s a personal choice. I don’t tend to think too much about who will see it afterwards, whether it will end up in someone’s house, in a museum, or who will look at that scene. The images I choose have great meaning for me. Sometimes I stay with a painting for one to three months. If I’m not doing something that’s important to me, I can lose interest in the middle of the process. I start a painting because I want to record something and I want to keep that moment. Sometimes, at the end of a work, when it’s on display in a museum and I see everyone looking at something so intimate of mine, I realize that it’s real and that everyone is seeing a part of me. But this thought only occurs to me afterwards, not while I’m painting. When I’m painting, I don’t think about who will see it, I just want to record it. If I had to paint just to stay in my studio, I’d keep painting. It’s funny how we change. I’ve always observed the people around me. You know that situation where you’re on a bus or in a restaurant and you start to imagine the life of the person next to you? I’ve always had this thing of observing and trying to understand their universe. I never imagined that one day I would be painting children. I was never the adult who liked being around children, but when I became a mum, my life changed completely. I spent almost five years without painting while being a full-time mum. In that period, my gaze was completely turned inwards, but I still had my mobile phone in my hand, recording what was around me. I was no longer looking at the people in the street or the city’s architecture. I was indoors, surrounded by the same people as always. When the pandemic hit, it didn’t change my day-to-day life much, as I lived in a bit of isolation. My studio is at home and the children also stayed at home. When I wasn’t being a mum, I was being an artist. The universe I share through painting may not be very planned, but it’s what surrounds me today. Perhaps when the children grow up, or if one day I do a residency in another country, other things will shine through. But I like to bring what attracts me most at any given moment. There are certain images that persist in my mind, almost as if they were insisting: “You need to paint me.” These images don’t disappear until I paint them. So, regarding the timeline of the images, they don’t all follow a strict chronological order. Sometimes a project may take priority, but the image that was left behind still remains in my mind. That’s why, even after a long time, I return to that scene – because I need to paint it.

You mentioned these images that persist, and paintings that can take a while to complete. How do you deal with the process of having an image or a design in mind and deciding when the time is right to finalize it and start executing it?

When I start a design, I’ve usually already invested a lot of time working on it. I’ve spent days on a single image, I’ve applied filters, I’ve done everything. However, while I’m painting, I’m also in dialogue with the painting. Sometimes the painting seems to say to me: “That’s not quite it yet” and, although I may not have a clear idea of what it will become, I know it’s not right yet. At times, I change the painting completely, but before that, I go back to the computer and explore various possibilities in the project as the painting develops. For me, a painting isn’t finished until I get to the end. So even if I have an idea of what I want it to be, the painting and the design are separate elements. That’s interesting, because I start the project thinking it’s amazing and end up thinking it’s rubbish (laughs), because for me the painting ends up surpassing the project.

At that point, does the project become a sketch of what the painting will become later?

Yes, it’s painting that gives me freedom. I feel that it treats me very well, and I treat it very well too. Even if I feel that the photo on the computer gives me all the possibilities to bring the painting about, it’s the painting that gives me the most back.

We’re talking about how each painting is a universe in itself. In a solo exhibition with several paintings, for example, do you create a conversation between the works? Or are you open to allowing a curator or gallery to create this dialogue?

I’ve never created a series of works (laughs). The works are always very individual. However, it’s curious to understand that, once I’ve completed a piece, it usually relates in some way to something I’ve already done. I’ve never determined a color palette or anything specific for an exhibition. What sometimes happens is that a painting from 2010, another from 2020, and one from 2023, end up appearing in the same exhibition because the curator thought they were related. I’m organizing my solo show for next year at Galeria Anita Schwartz [September 2024]. I need to choose some paintings for the exhibition, and I want it to have the feel of a Sunday afternoon, so I have lots of possibilities. A Sunday afternoon could be a barbecue at home, a day out with my children and their cousins in the countryside, or even a family trip to the beach. But for me, Sunday is family day, when we try to get together for lunch. I want this exhibition to convey that feeling. The challenge is deciding which images to create because I have everything already here.

From my personal perspective, your paintings are very inclusive of the viewer. Although I don’t have children, when I look at some of your paintings, I feel the same joy I felt as a child playing with my brother. I can visualize the happiness of one of my sisters, who is a mother, with her children – my nephews. So, for me, your paintings create an atmosphere of inclusion, in which joys and feelings are shared. Recently, Sunday afternoon has become that special moment when we carefully choose the friends with whom we want to spend time, rest, and recharge for the week ahead. On Friday night, you can invite everyone you know, but for Sunday lunch, we carefully choose the friends to share the moment with.

I would say that I really put myself into my painting. Even when I’m portraying my children, I try to bring something from my own childhood. For example, there’s a game called “fish-fishing” that reminds me a lot of my childhood. If I had to choose a moment to represent them playing, it would probably be them playing “fish-fishing.” I like to include elements that are more from my childhood than theirs, but it happens without me realizing it, because they are things that interest me a lot and which I want to incorporate. I think this ends up making people identify with my work and feel closer to it, because it refers to moments and people from their own childhood. I questioned for a long time whether the intimate and personal nature of my work could evoke emotions in others. I even asked myself: “Would anyone want to see a painting of my grandmother in bed? Or my son sleeping with my husband?” (laughs). In a way, I don’t carry much of the popular Brazilian universe in my work. I end up including “gringo” aspects, from outside Brazil, since my universe was built dynamically, with various influences around me; Brazilian, Japanese, and international. I always wondered if people would be able to connect with my work, and that answer came when they started to say that they identified with what I was doing. I get told stories that sometimes move me. One day, a girl told me that she had seen my work and said: “You know, I never knew my grandfather. He had already passed away when I was born. But when I saw the image of your son with his grandfather, I felt as if I had lived that moment.” She thanked me for making that painting and that’s very powerful. You do something because you saw a scene that marked you in such a way that you wanted to record it and it touched someone you don’t know, at a time when you weren’t there, because they felt they had lived a scene they hadn’t. It’s very nice. It’s really nice.

This is one of the great aims of art: to take us beyond ourselves, allowing us to discover new ideas and thoughts. This involves exploring a non-existent memory and the feeling of nostalgia for something that never happened. In abstraction, we find an easier way to navigate these feelings than in figurative art, which seeks to involve the viewer in the scene. Your works contribute to this immersion because of their large dimensions. How do you decide on the scale and size of your paintings?

When I started painting, my brushstrokes were clearly marked and thick, and it was difficult to work on a small scale. That’s why the size of the canvas never intimidated me; I needed space. Over time, I realized that when I painted a portrait that was smaller than life size, it seemed too small. After making several paintings, I began to understand how each one spoke to me and whether it was right or not. I don’t like to paint the same idea more than once. If I’ve created an image, the painting is specific to that image, and a new painting will come from a new image. I don’t usually redo a painting I’ve already completed because I don’t see the point. However, sometimes I look at the finished painting and think that it could have been bigger. It seems that the painting would have been more right if it was bigger. I began to understand that, for me, the proportion of the image should be at least the actual size. To define the size of the canvas, I print the face at the size I intend to paint, to see if I feel comfortable with it or if it should be bigger. When the painting has several characters in perspective, I always check the size of the face of the character furthest away, in the background. If the character in front is too big, that’s not a problem for me. However, if the character at the back is much smaller, then we have a problem.

Would you say that perhaps the relationship between the painting and the viewer influences this question of size?

Actually, the focus isn’t so much on the person watching, it’s on me. That’s intriguing – the painting is an extension of me. It may sound selfish, but for me the painting is mine (laughs). It’s a very intimate conversation with myself. I’m not so concerned about people’s reaction to it, but rather my own.

How do you feel about the process of sharing your painting with the world and, in a way, saying goodbye to it? Do you handle it well or do you end up keeping a lot of them?

I feel a strong attachment to my paintings while I’m creating, thinking that I’ll never be able to let them leave my studio. However, when I finish, I understand that they need to be shared with the world and that keeping them just in my studio wouldn’t be right. At the same time, there are certain paintings that I’m very attached to and that I prefer to keep to myself, having no intention of selling them. For example, in one of my first paintings, I depicted my grandmother in a loose, unpretentious way. It’s not that good technically, but when I look at her, I know where I’ve come from as a person and as a painter, and if I need to go back to that place, I know I can. If I’m interested today in painting that is more meticulous, more detailed, I know that a lot of me is in those loose paintings. Although I have many paintings that depict unique moments with my children, I don’t worry about letting them go. It’s gratifying when they find a new home, and the responses I get from people make me happy. I know that even though my paintings could end up anywhere in the world, they will always have a connection with me.

You seem to have a strong and healthy connection not only with painting, but also with your children. Has motherhood changed your relationship with painting in any way?

I’ve never had a problem letting my paintings go, but, of course, it’s always easier to see a painting of a friend go than one of a child because I knew there was something there that wasn’t entirely mine. When you’re a mum, you feel something that belongs to you, in a way. I realize that one day my children will go out into the world, but there is still that feeling that they are my little children, my babies (laughs). It may sound cheesy, but the phrases you hear from a mum, such as: “A mother’s love is indescribable and unlike any other love,” turn out to be true. Motherhood brings so many new experiences that you inevitably end up taking many of them into your life as a whole. I’ve translated many of these new sensations, responsibilities, and tasks into my life: this new way of dedicating myself to someone other than myself, thinking about the community, the place where I live, and the people around me. Things that, when we’re young, we might not question so much because we’re more focused on ourselves. But when you have children, it’s no longer just about you. It’s about what you’re leaving behind, where you want your children to grow up, who you want them to be in society. You start to think more broadly. There’s something about seeing your painting go, feeling that it doesn’t just belong to you but also to the world, in a sense. You learn to see beyond yourself, to understand community, the human being, and society as a whole. This doesn’t necessarily have as much to do with becoming a mum and reflecting this change in your work as a painter, but motherhood changes you in a way that ends up bringing about inevitable changes.

I’m thinking how we, as a society, and our everyday systems, are built on patriarchy, and that, as a result, we end up excluding many experiences and the feeling of motherhood. Your paintings share feelings of motherhood, allowing even those who are not mothers to understand these emotions that permeate a given scene. This helps us to learn and incorporate these experiences into our lives.

I think the point of my work is not so much about motherhood as it is about care, affection, understanding, and loving others. And this is something accessible to all of us, even if you don’t experience motherhood in your life. Whether you’re a mother or not, there’s something there that you feel and understand, a feeling that you recognize. I don’t think the real problem is that we grew up in a patriarchal society, but the lack of appreciation of care in society. It’s also interesting to consider this in the field of politics. I believe it’s crucial to have more women in politics – not just because they’re women, but because we’re able to approach issues from a less individualistic perspective. We have a more collective outlook. It’s not just a gender issue, but perhaps it’s because the expectations placed on women from childhood are different from those placed on men. As the mother of a boy and a girl, I understand that the educational challenges are different. For example, I don’t have to emphasize so much to my daughter that she should be empathetic, that she should be friendly with her classmates and that she shouldn’t hit anyone. Sometimes I do, but it’s not the same approach I use with my son, because they have different behaviors from an early age. In this case, as a mother I have two options: encourage my son to defend himself and fight back more aggressively or teach him the same way I would teach my daughter, explaining that aggression is wrong and encouraging empathy and affection. Perhaps the biggest issue we face regarding gender differences is machismo, the idea that men should be rough and big, unwavering providers. From an early age, certain expectations are placed on boys and girls in different ways. When I became a mother, I realized that one of the most revolutionary attitudes we can have is the way we raise our children. Children learn to be human based on who is around them, the examples they see, and the things they are told. That child will one day be the adult who creates laws, who can stop or start a war, the adult who decides to prioritize the economy, or health. Today, I understand that being a mother is a social role that I have as a carer and as an educator of this little being who will become an adult.

It’s certainly not an easy task. As we expand care and education as something social, the more we emphasize the fact that this is everyone’s responsibility, not just that of the parents.

Yes, it’s society’s responsibility, the responsibility of the carer. The politician, in essence, should be the one who looks after society. It’s the person we put there to look after us, after our interests.

Marjô, it’s amazing to talk to you, as many of the subjects we discussed are very present in your painting. Thank you for sharing these intimate images and feelings that are not easy to transform into a painting in a contemporary art context, where confrontation is sometimes easier to observe. Your paintings have a conceptual weight and strong emotion, conveying positive feelings of welcome that go beyond the family nucleus and encompass care and love.

Thank you very much. As you said, confrontation is more media-orientated and attracts more attention, and subtlety is, by nature, subtle, so it’s difficult to find space to discuss it. I feel very grateful to be doing something I love, sharing something I believe in and, in a way, being heard without having to shout. Today we have so many ways to shout, to talk about a subject, but every time I address a topic, I feel that I enter a place of responsibility. For example, there are various ways of talking about a war, and the most common is through its atrocities. I understand that there is the aspect of confronting and generating revulsion with such scenes, but what is my responsibility as an artist in adding one more such image to the world? Do I have another way of talking about this feeling, about what we’re missing or what we’re not paying much attention to? I have many thoughts, good and bad. Sometimes I have more nightmares than dreams. If I were to translate what’s on my mind, I’d have a lot of negative things to show the world, but I’d be strengthening those bad images. As an artist, I feel that we should value our humanity beyond what many consider talent because it’s not about being competent in our artistic endeavors, producing technically perfect works, but about what is truly human within us. That is the greatest gift we can leave for others.

Interview made on 13 November 2023 remotely via Zoom

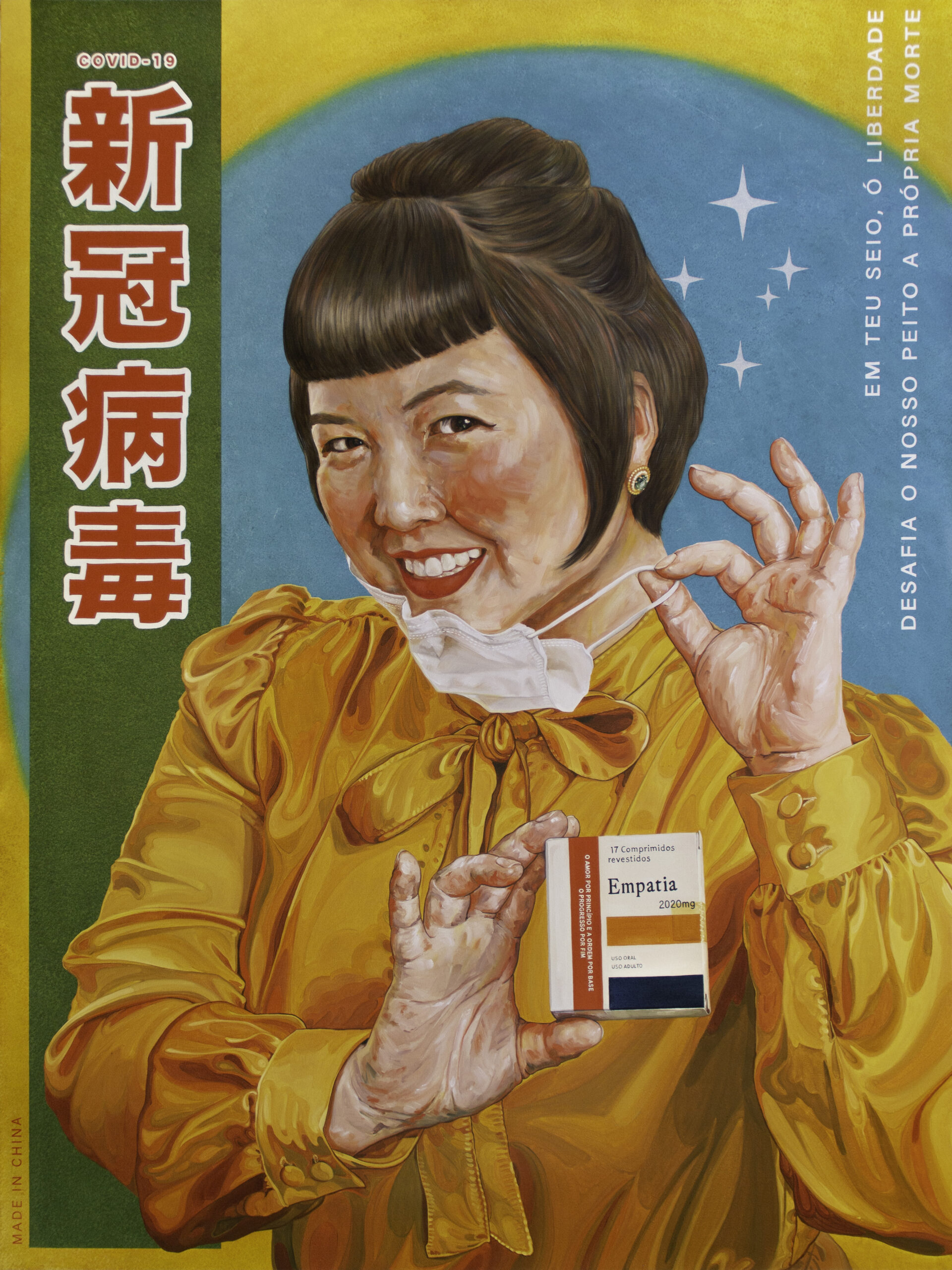

(Self-Portrait)

Oil on canvas

160 x 120 x 3.5 cm

2020

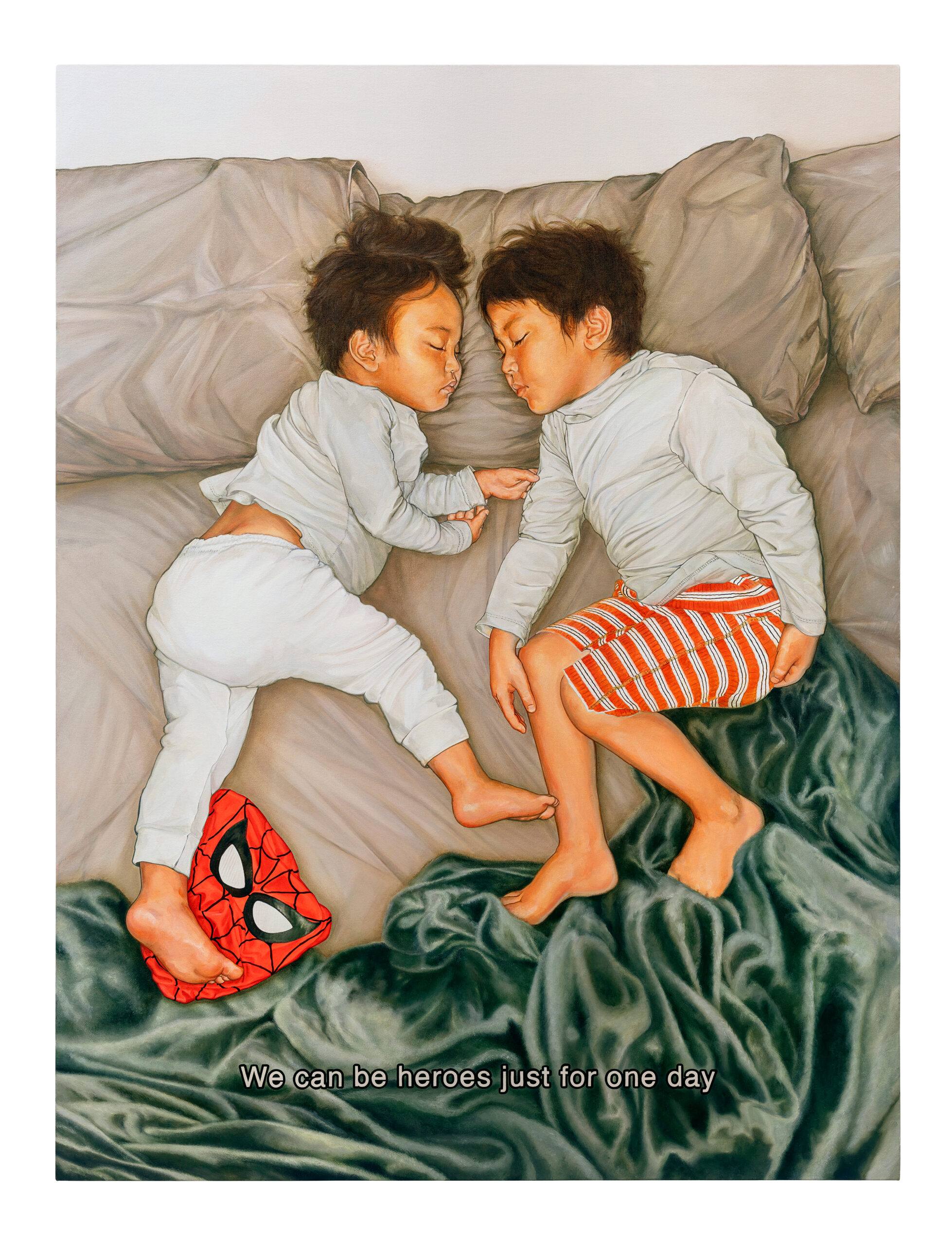

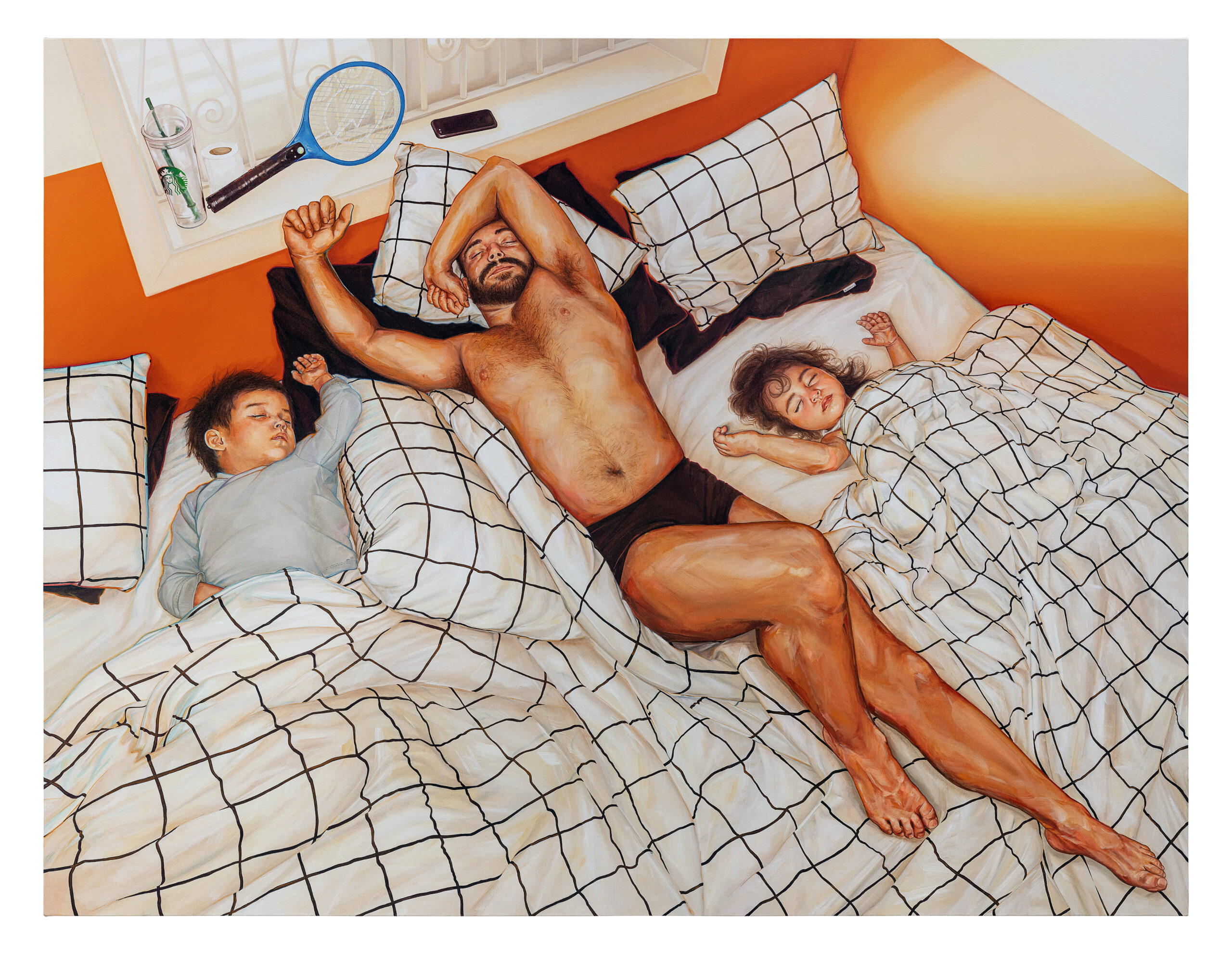

(Leon Mizumoto Gomes and Pedro Gomes)

Oil on canvas

120 x 100 x 3.5 cm

2021

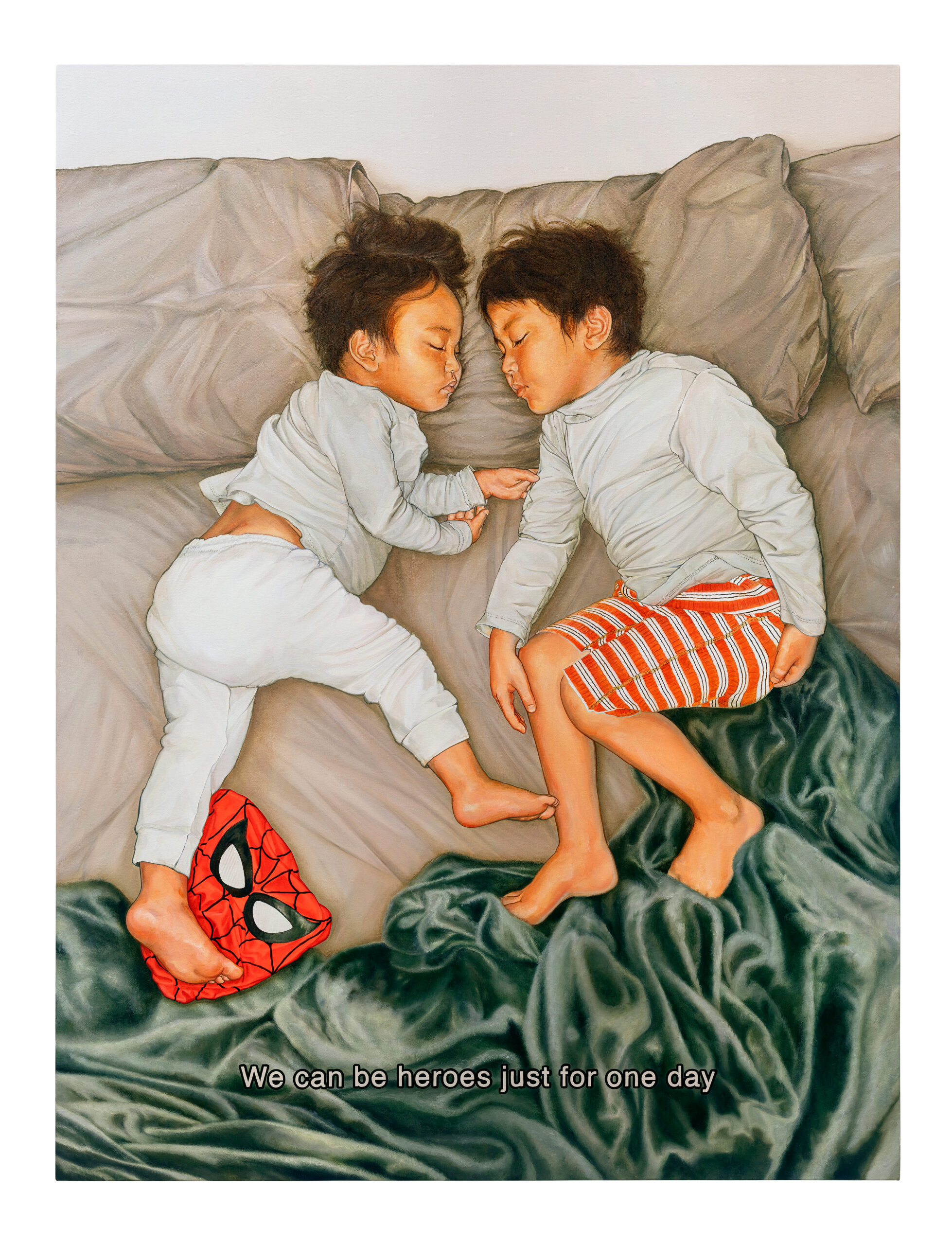

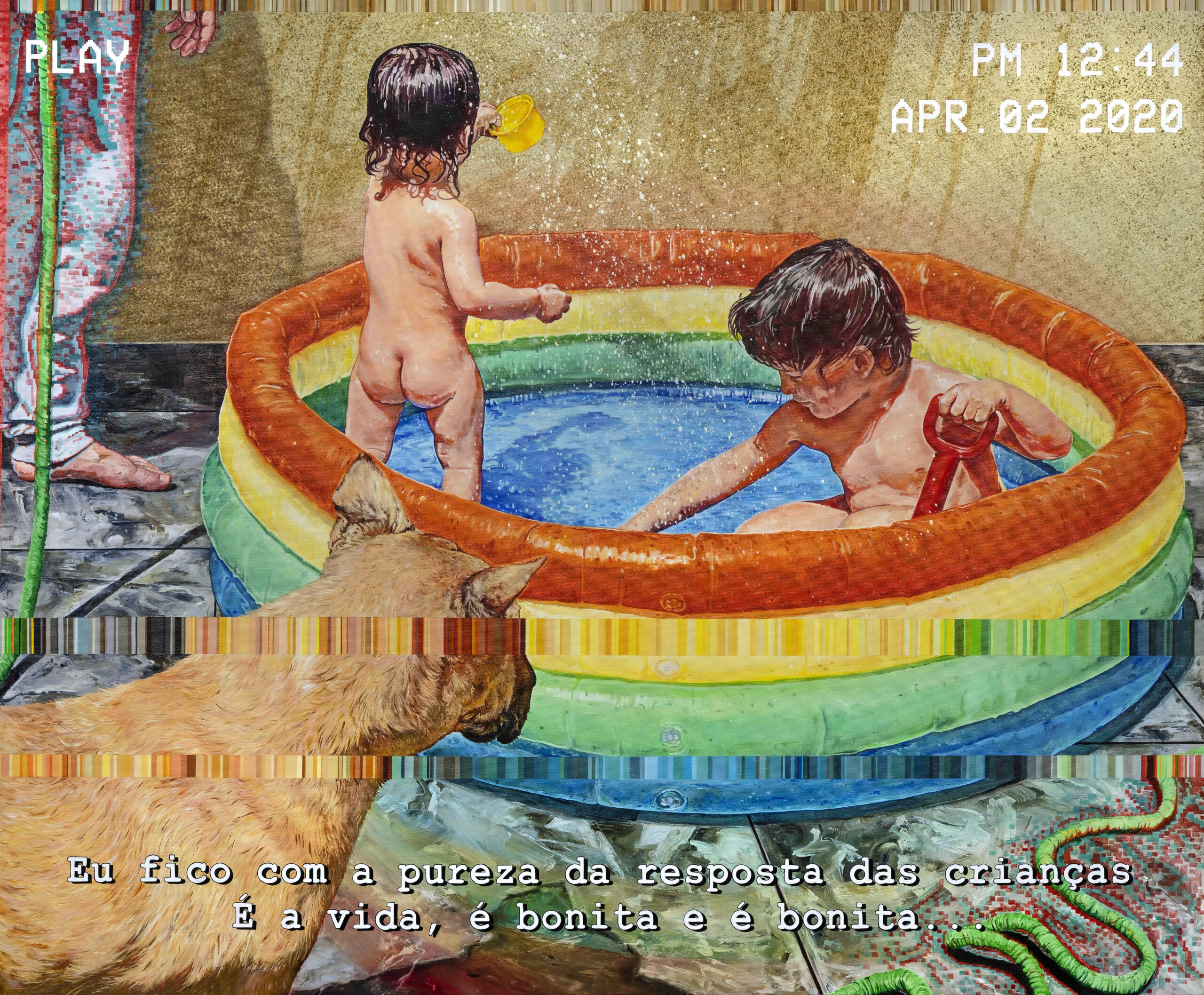

(Lui Haru Jorqueira Nakumo and Tom Inari Jorqueira Nakumo)

Oil on canvas

180 x 135 x 3.5 cm

2022

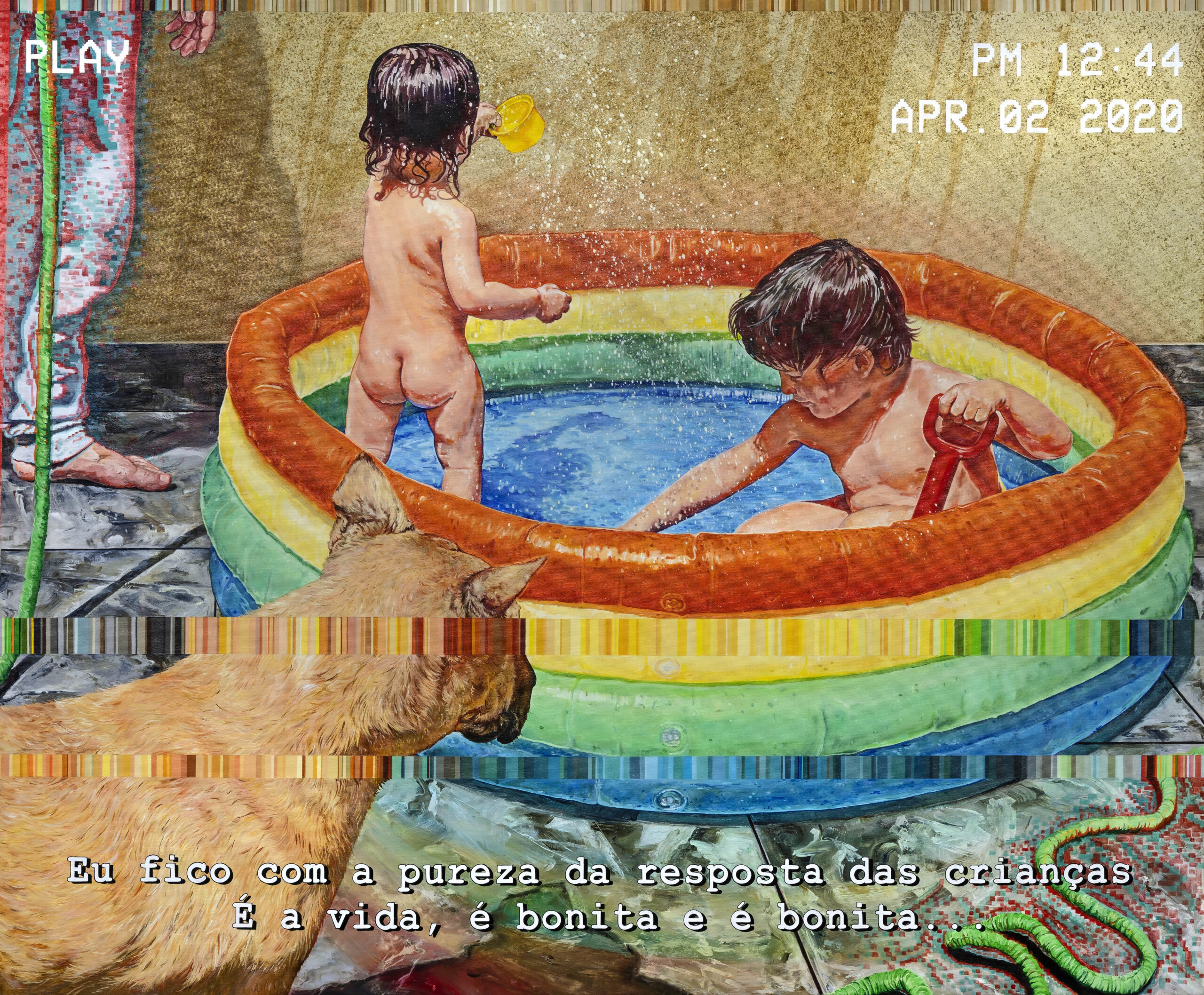

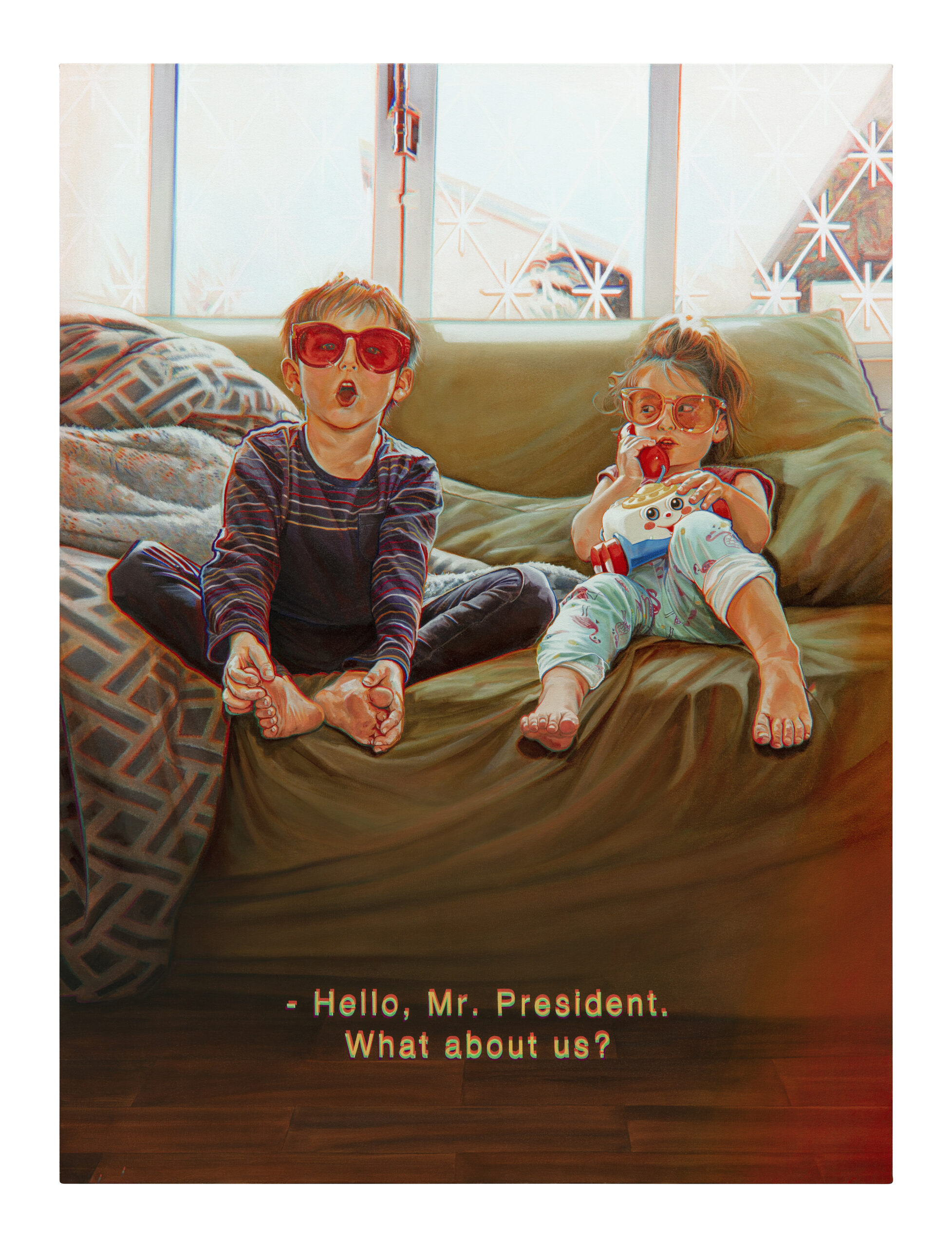

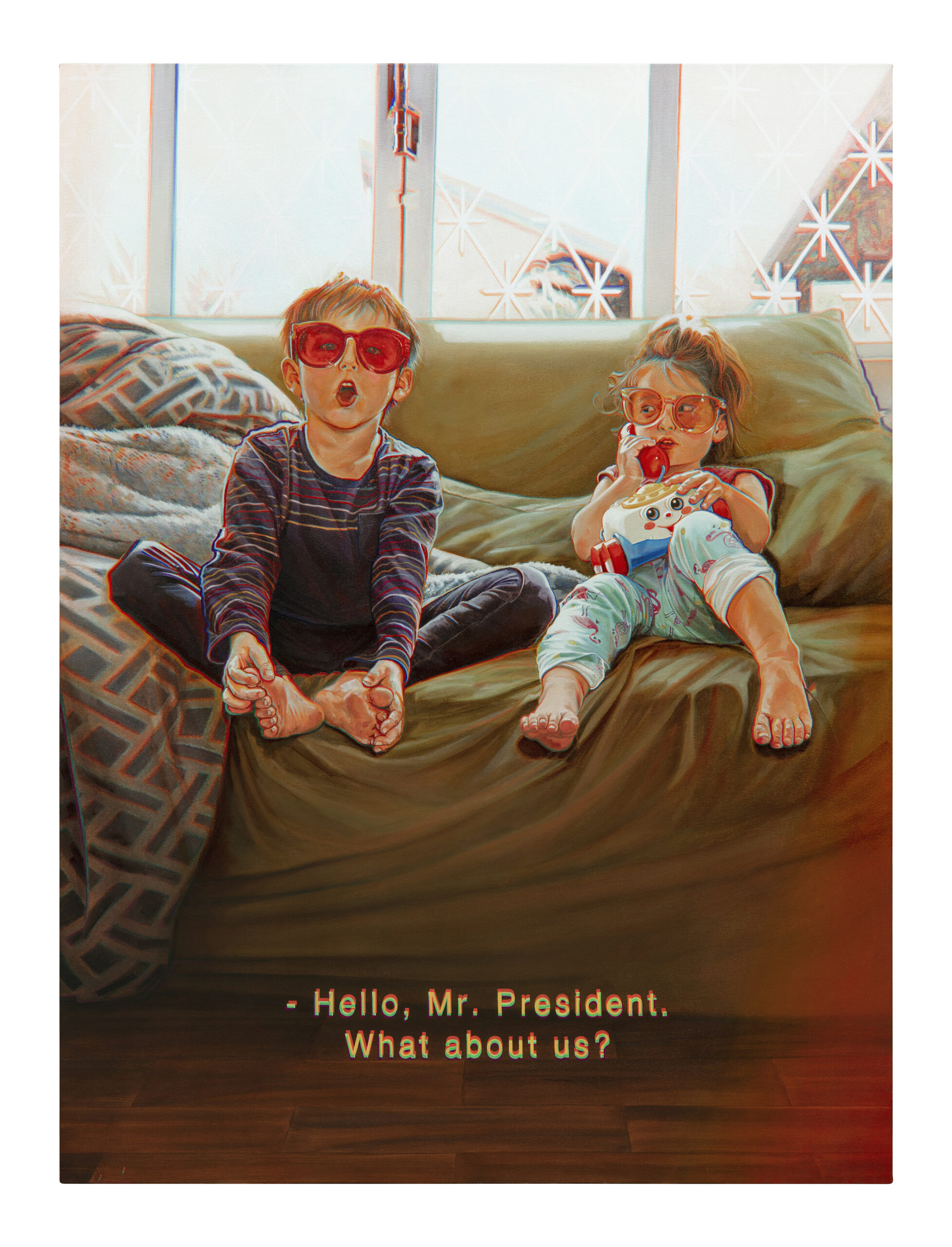

(Leon Mizumoto Gomes and Marie Yuki Mizumoto Gomes)

Oil on canvas

180 x 135 x 3.5 cm

2022

(Tiseko Yamaguchi)

Oil on canvas

120 x 160 x 3.5 cm

2021-2022

(Leon Mizumoto Gomes, Francisco P. M. Gomes

and Marie Yuki Mizumoto Gomes)

Oil on canvas

190 x 250 x 3.5 cm

2022

(Leon Mizumoto Gomes and Marie Yuki Mizumoto Gomes)

Oil on canvas

100.5 x 120.5 x 3.5 cm

2020