Celina Portella

Celina Portella, a dancer and visual artist from Rio de Janeiro, investigates the interaction between the body and the image in space via different techniques and formats. In her works, which include videos, photographs, and installations, the artist makes extensive use of her own body as an instrument to provoke reflections on the female body, perception and identity. In the interview, Celina explores her analogue approach and discusses the choreographer’s gaze she develops in her works, also highlighting the playful character that permeates her compositions. Check it out:

Celina, thank you very much for being with us today. We’d like to start by asking you to introduce yourself, sharing any information you consider important about yourself and your work.

Thank you for inviting me! I’m Celina Portella, a Brazilian from Rio de Janeiro, and an artist and dancer. I’ve had a long career in dance – that little girl thing that parents put me through at school from an early age. I started working professionally very early on, giving classes, dancing in companies, etc. At university, I started studying graphic design, but I realized that wasn’t really what I wanted, and then I studied fine arts. In practice, I started making work in dance, because I was already dancing professionally, and I started making films in Super-8 format. For a while, I worked with the Lia Rodrigues Companhia de Danças, making my own work at the same time. I travelled a lot, moving through many different environments and circuits, even though they were close to each other. I’m the kind of person who always wants to be in new places, and to get to know them. After spending some time in Rio, I ended up coming to São Paulo. At the time, I wanted to do a master’s degree abroad, but it didn’t happen, so I decided to come to São Paulo. I love Rio, but I’m enjoying living in São Paulo. I had my son and then the pandemic hit, so I’m still enjoying getting to know the city, even though I’ve already been here for five years (in 2024). Along the way, my work has developed through the different experiences I’ve had. Let’s talk more about that now…

You mentioned that you’re a dancer. How do you perceive the influence between your dance and artistic practices?

I started mixing things up by making films with Super-8, involving movements created for that type of camera. I worked in a duo with another artist, Elisa Pessoa. We made a few films, and, over the years, we realized that we were making work that had a unity. She filmed me dancing and they were somewhat absurd, somewhat improbable images, a dance for the camera. There was no narrative telling a story, but it was very much permeated by dance, or some kind of action or movement. Those were the first works. Then digital began very strongly, and I started working with the projection of the body in life size onto certain surfaces, and sometimes re-shooting this, creating layers and textures in a digital image, which, for me, is very difficult. The analogue camera – Super-8, analogue film – has an aesthetic that interests me and is very beautiful. I got used to digital but the more perfect and “clean” the image becomes, the less interesting I find it (laughs). I started paying attention to this aesthetic issue of film and image, and playing with it. I think that, right from the start, in my films where there is dance, I wasn’t just talking about dance. In fact, nothing is ever just one thing. I’m very interested in the freedom you have in the visual arts to be able to research whatever you want, regardless of the language or technique you’re using, and to be able to deconstruct them. In other contexts, this is also possible, but for me, the visual arts interested me the most. There isn’t much separation for me, but what I realize today is that my work has developed from a choreographic perspective. At first, I worked a lot with video, site-specific, with the projection of the body. Then I started migrating to the canvas, with the body interacting with the canvas frame, first in video and then in photography. I also started doing more work for institutions, so it was work created for that specific space. For a long time, I didn’t work with galleries because they were bigger projects, with machines, videos, video installations. However, I began to think about the appropriate format for being in a gallery. I believe it’s important to be in different contexts – in the gallery, on the street, in the studio, at fairs, in the market, in the institution, in museums and in independent spaces. That’s why I started thinking about a format that would also be in dialogue with the gallery. That’s when I started producing photographs that, like the videos, had a strong relationship with the body, dance, and the materiality of the image. In most of my work, I’m the one who appears in the images. As I’ve always danced, I know how to do the things I invent and I used myself, because it was more practical and precise. But I don’t just want to talk about myself, I want to talk about women’s bodies. Nowadays, I’m not dancing in companies, but for me the question of choreography, of the choreographic gaze, which is the writing of the body’s movement in space and in that specific space of the video or photo, is and always will be very evident and present. If, for example, I’m interacting with the frame, I have to know what I have to do to make the idea work technically, the timing and choreography of the camera, etc. Of course, photography is sometimes easier because it’s static. In video, some jobs were quite challenging, where I had to think about how the idea I had would work in that format.

It’s interesting to consider that, although photography is static, it’s necessary to capture and represent movement in an image. For example, when talking about your experience with choreography, I can see this in your “Cut” series, through the movement of the arm indicating the action that took place to result in the cut.

I like the idea of performing actions rather than interpreting something. Even if there is no interpretation in the sense of creating a character, when you move for the camera you are always creating a choreography and interpreting movements, and this depends on the level of experience you have. In any kind of movement technique, if you have more experience, you’re more prepared in terms of how to make a certain movement, or at least you’re more aware of what movement you’re making and how it’s going to look. So when I say that it’s easier with still images, it’s because I can take and retake photos until I find the result I’m hoping for. But even if I can do it again, there’s a limit too. The ideal is to immerse myself in the performance and take the photos without so much control. Sometimes, I stop for a while to check that the material is coming out the way I want, from the framing, the angle etc., which can be very specific depending on the project. In video work, it’s more important to get things right quickly. It’s often complicated to keep repeating it. Sometimes, you do a 10-minute take, you look at it and it’s not good, you have to do it again. In cinema, for example, there’s a whole team and a lot of money invested in the shoot, so everything has to be right first time. In video art production, there’s a contradiction: because it doesn’t involve so much structure, there’s a bit more freedom, but at the same time it also has to work right away, because there’s no money to redo things. For me, this makes the performance/movement and its “ephemerality” present in the work. Even if an action is recorded on film, video, or photo, and even if the work isn’t a performance record, the performance that took place for the work to exist is visible in the image, even in the still image.

How do you describe your relationship with performance?

Performance is not the final language of my work, but it is within it. When I film or photograph, what happens for the camera only happens at that moment and you can’t keep redoing it a million times. There’s something ephemeral about it that’s essential, even if it’s filmed, photographed, or recorded. But in general, the base is a video, a photo, an installation, a video installation, not a performance.

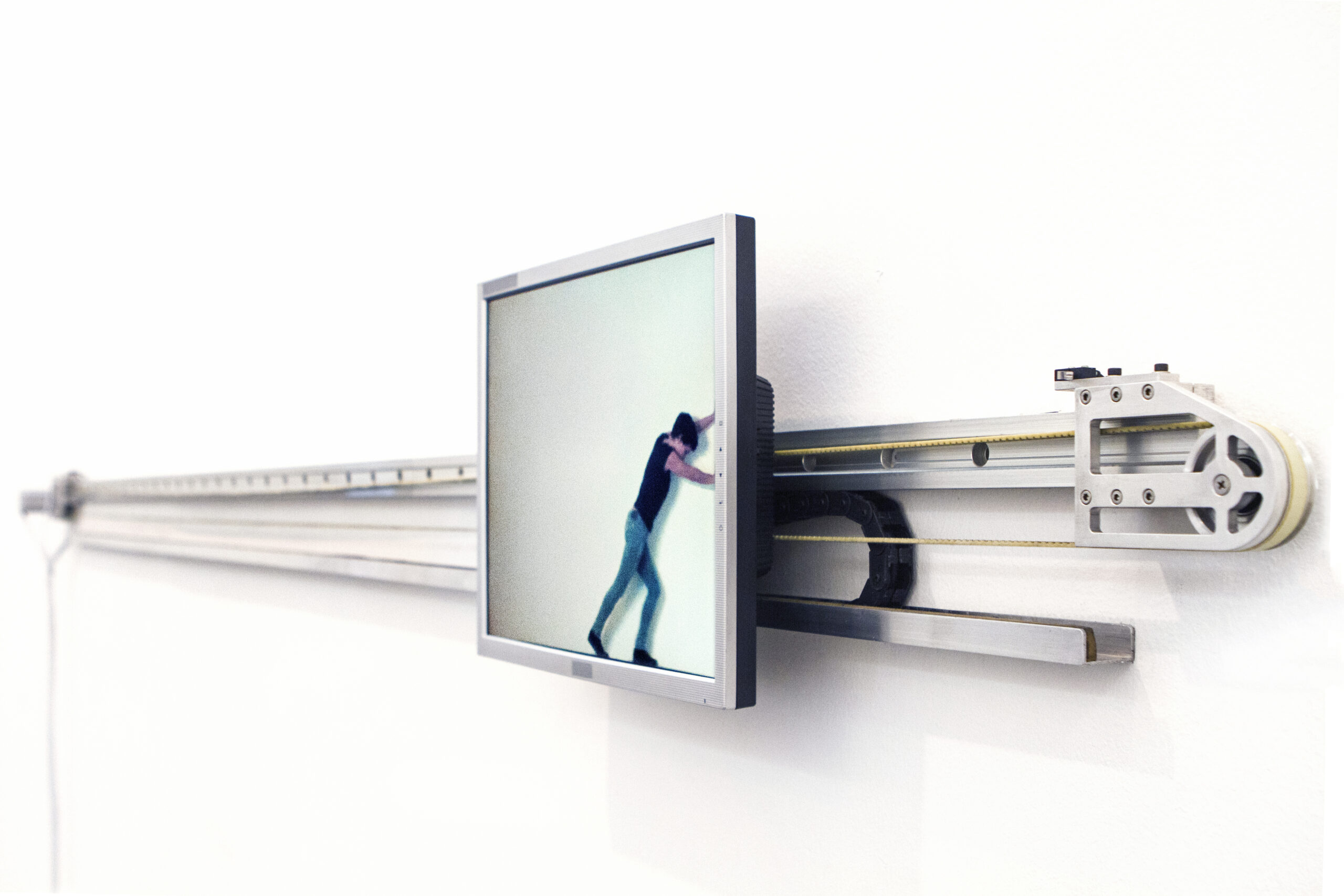

There is a trace of performance in the work, perhaps due to the body, which makes reference to movement. Thinking about the work Movimento², it’s a challenge to classify it because it’s a video, but it’s also a sculpture. It’s not a performance, but it presents itself visually as such. My reading would be something like a recording of a performance that becomes a performance within the context of the mechanics that move the screen.

It’s because there are two different things: the documentation of performances, which is when the artist is doing a performance, and it’s being filmed. It’s documented on video, which goes into the museum, the gallery, etc. In the case of Movimento², it’s not just the documentation of a performance. I filmed a very specific movement for the camera, to create images that would be presented on that base/object that also had specific characteristics. That’s why I call this work a video object. I also classify it as a video installation. The performance took place at some point when filming the video, but it’s not the final language of the work. In this series there is a screen that moves on a horizontal rail, another on a vertical rail, and some that are fixed, where the body appears in different dimensions. With more or less space, I end up moving in different ways in each video object. This work involved calculating area, distance, and speed. I had to do some math; it was a crazy job. For example, if I took 10 steps to the right and 15 to the left, the screen would come off the track. I had to work out how many steps I needed to take to fit the size of the rail and how fast the steps should be, among other things. I started working with photography and editing, and all that, in a very self-taught way. Suddenly, I found myself doing math, which, although simple, I didn’t really remember because it was from my school days (laughs). In this work, the video and the editing take me into a mathematical universe. The work takes you in many directions when you are doing everything. You can always hire someone to do it, or to solve technical issues in your work but in this case, I did the calculations myself because I could. As for the programming and mechanics, I relied on the work of other professionals. In any case, it’s always necessary to understand how each thing works so that the work itself can happen.

Yes, it’s interesting to see this symmetry and synergy between the body and the media in your work. For example, the life-size hands praying, and the photographs in larger formats. Sometimes we look at video and think it’s super easy, but actually, it’s not. There’s always a negotiation between the body, the video, and the way the video will be shown.

It’s funny because, nowadays, everyone has access to both video and photography, much more than before. Sometimes, you’re going to make a video and show it at an exhibition, and it ends up being crazy because, depending on the video format, the Codec, the HD that’s going to be playing on the TV, the TV, what format it accepts, etc., the video may simply not play. I know these are technical aspects, but it all comes down to work. Presenting an ordinary video may or may not be easy. Presenting a video object, or a video installation, is more complex, especially when the image and the medium are inseparable and codependent. Video has always been inserted in a context of new technologies. I started attending events related to this and thought, “I have nothing to do with new technologies, I’m a dancer” (laughs). I’m not the most computer-savvy person in the world. There are people who can watch tutorials and solve everything, and I think that’s amazing because it makes life easier. But the technical side isn’t what interests me most.

Eu costumo dizer que meu trabalho é analógico, mesmo que eu use tecnologia para fazê-lo. Por exemplo, quando faço a projeção do corpo em tamanho real, que eu projeto, filmo novamente, projeto, filmo de novo, aquilo vai criando camadas, mas isso é feito sem efeitos digitais.

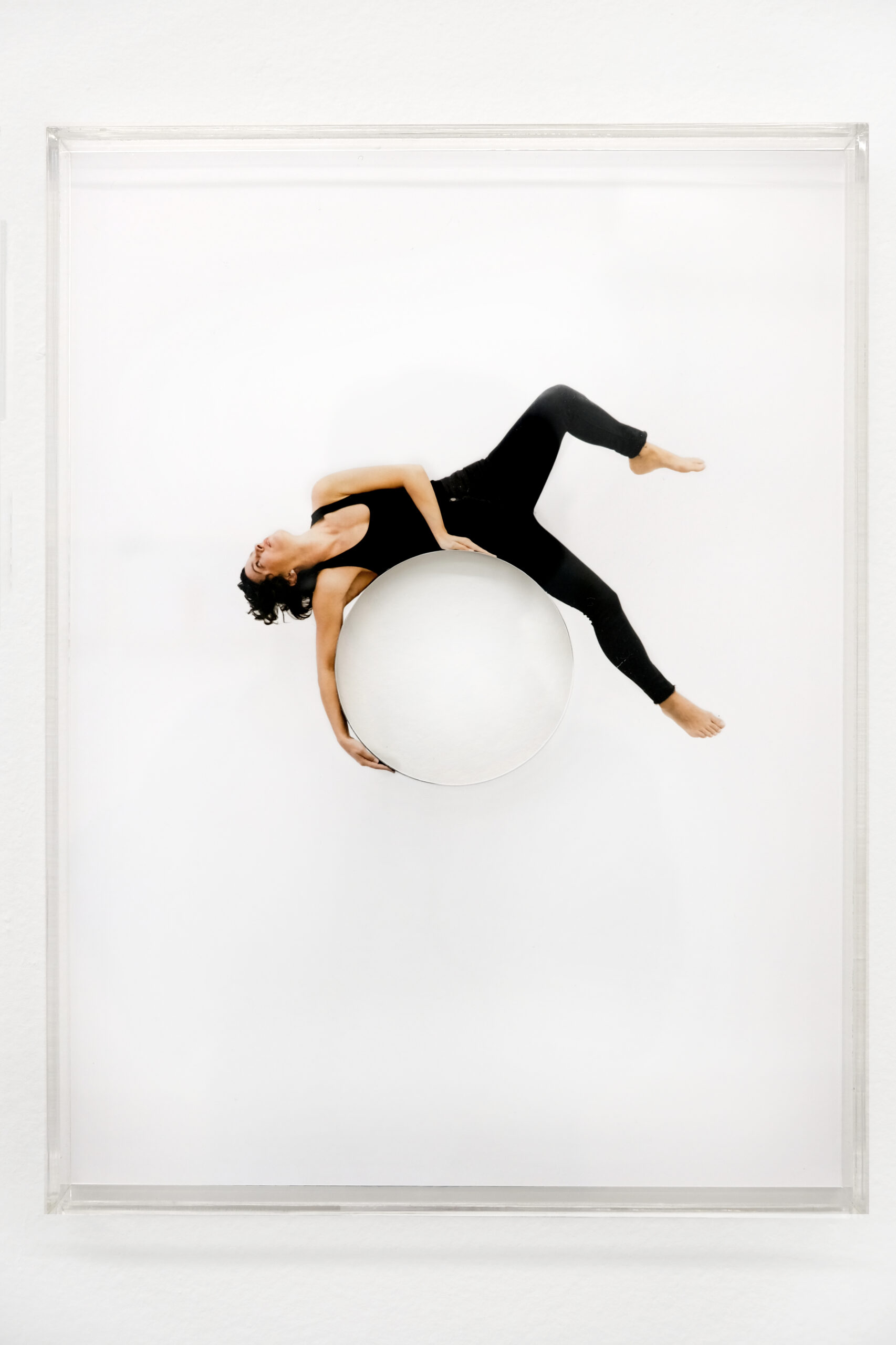

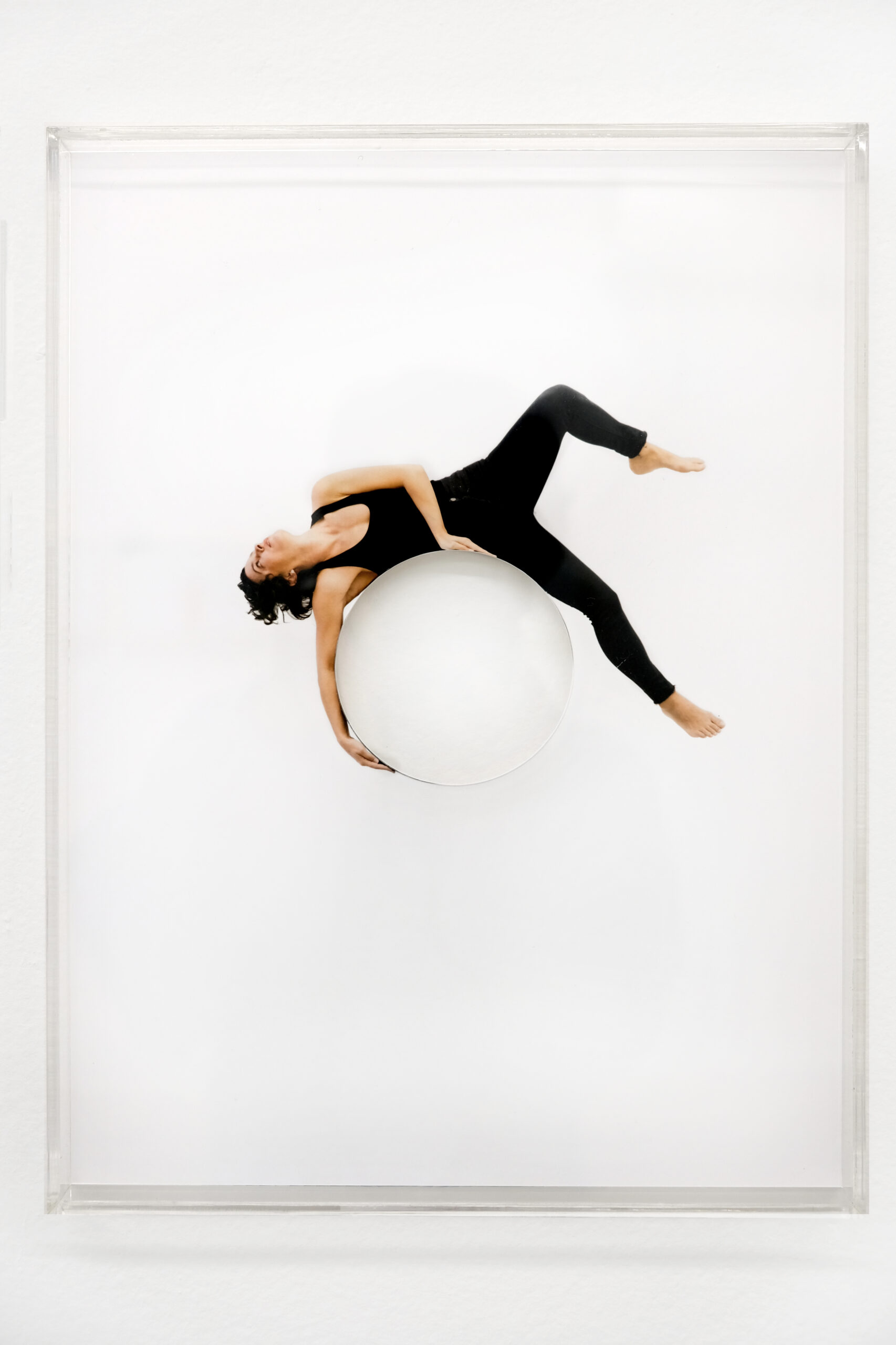

(Translation: I often say that my work is analogue, even if I use technology to do it. For example, when I make a life-size projection of the body, which I design, film again, design, film again, it creates layers, but it’s done without digital effects. Often, people come and say, “there’s a Photoshop effect that will look great,” because in Photoshop you can build up several layers, but it’s not about that. I have a more recent work, a series I call “Photo-paintings”, which are photos of my body relating to a square, a rectangle, and a circle. I made some iron objects to attach to the wall and create the pictures. Then the object disappeared, and I painted those shapes. I wanted to do something in which the body related to the painting as matter. I could make an effect and put it in Photoshop, or lie down on the floor and shoot from above, so I wouldn’t have to use those objects, but by using them, that performance, that situation with that format, really happened. I was actually interacting with the shapes, and that makes a lot of difference to me because it’s my research. So, in that sense, I say that my work is analogue, because almost everything is real, it’s a kind of analogue effect. Sometimes I clean up the photo a bit, but I don’t make montages or animations. In the rail work, one of the videos is a 12-minute sequence. If I happened to miss a step it would go wrong, and we’d have to film it again. The screen goes to the end, to the middle, to 1/4 and 3/4 and back – it’s a real choreography on the rail.

Exhibition view – Hélio Oiticica Municipal Arts Centre, Rio de Janeiro

Many of your works have a playful quality that amuses and fascinates. Where does this interest come from? Is it something that just happens, or that you intentionally try to create?

I think it’s something that just happens. The works flow from one another. I made films with Super-8, then life-size projections of the body, and from then on, I had to fit the 2-D image onto 3-D surfaces, so I started thinking a lot about the limits and support of the image. It was from there that I moved on to the canvas, the frame, and the paper support. One thing led to another. My work is presented in a way that people can understand it without the need to study to understand it. The question of playfulness has an aspect that I think is good. People don’t understand how the piece works and keep trying to figure out what the trick is behind it, but then anyone can understand, because they are simple analogue devices. In that sense, I’d say it’s a popular work; it’s easy, and lots of people from different backgrounds can access it. Although a playful quality also fits the work, I identify more with ironical characteristics. I’m talking a lot about movement, perception, and women’s bodies, and, for me, in this way, I’m talking about politics. Everything is political, but the work doesn’t have an obvious political discourse – it has some layers behind the ironies, the playful things, it has multiple meanings. I don’t want to be ironic, funny, or anything like that, but I think it’s part of my way of communicating.

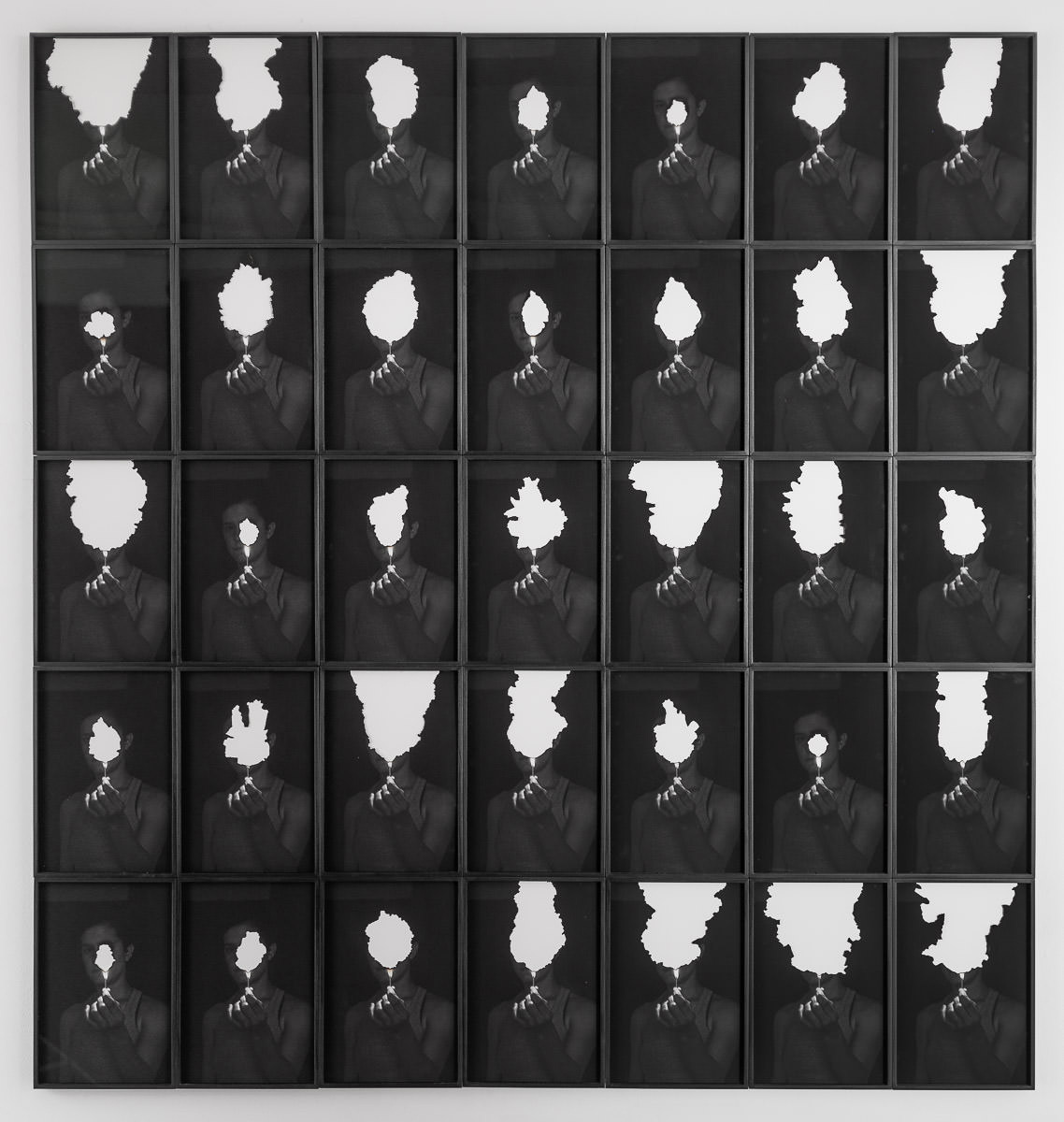

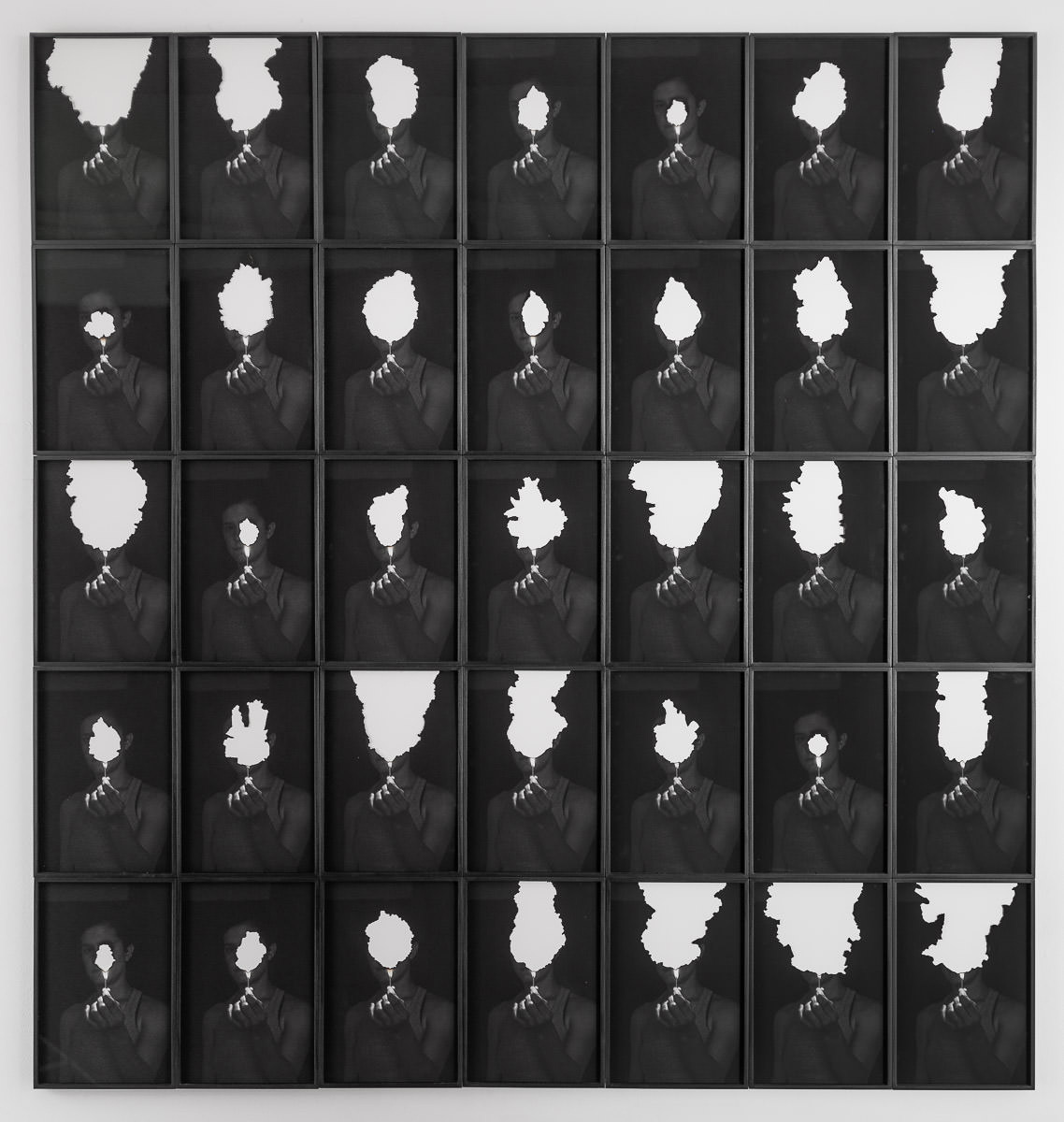

In the Fire series, it’s remarkable that a female body, a female face, causes the destruction of the image. From a political point of view, this gives power to the passive figure, whether observed or photographed, male or female. This passive figure takes action in its own representation.

Yes, the Fire series has the images I call “burnt”, which are photographs of my torso burnt multiple times, creating different shapes. There’s the work Fire-Fatigue that’s s a video in which my image also starts to burn, and we see flames, and there are also some diptychs in which one photograph is burnt and the other is a photo of the image itself on fire. One is the matter already burnt and the other is the matter on fire, but it’s just a photo of the matter, it’s not the matter itself alive there. Destroying one’s own image, one’s own representation, and therefore the representation of a woman, is an iconoclastic act, in which destroying is also creating something new. When the represented figure takes action, it ceases to be passive and already represents something different. When we’re talking about the figure of a woman, this directly raises feminist issues. In the Fire video, I project onto a piece of paper and burn it at the right moment, so I also have to perform a choreography because I know I have to synchronize the action I’m going to do with the action that was done in the video. It sounds complex, but it turns out to be very simple and creates an effect. It’s strange, people ask, “Wow, but what’s burning where?” I think it’s a questioning of perception. This is what we’re discussing most nowadays, especially because of social media and access to photography. The representation of truth is the great question of art, of seeking the real, a portrait of reality. We have parallel realities; everyone creates their own. There is a consensual reality when we make pacts or agreements so that everyone believes more or less the same things, but reality is completely relative. When it comes to social media, which a central issue today, the idea that images represent reality can be very dangerous. We need to think about how to take a critical look at what we’re seeing. People look and say, “Wow, that’s absurd” without even understanding the situation. We can still tell when it’s a photomontage, or at least we know that photography doesn’t guarantee that what we see in it is real because we already have a lot of access to photographic production and many people know how to use Photoshop or image editing apps. But now, with deep fakes, people have totally bought into the idea of reality – because these are videos, they believe that the images are reality. I think that, when I question what the viewer is seeing, it’s a way of drawing attention to it all.

In the series of photopaintings, the painting on the wall ends with a photograph of the hand holding the brush. When the visitor sees the stroke, they think it was made by someone else, perhaps the artist, but when they see the photograph, the viewer is challenged. That real perception of the stroke changes, because we don’t know if it was really the artist who made it. The painting leads us to the conclusion that it is the photograph.

Yes, even though it’s an obvious effect, it raises these questions. You think it’s one thing, but it’s not. You know that the stroke wasn’t made by that hand in the photo, but it still allows you to fool yourself. It’s not just an effect that connects the real painting to a photo that claims to have made the painting, I think it goes beyond that. You’re surprised and question what you’re choosing to see, or choosing to believe, because you obviously know it’s “fake,” This makes me think of the work Público, which I did at the Arts Triennale at Sesc Sorocaba, which is an interactive video installation. It’s a closed room and, when the viewer enters, they’re standing on a stage. In front of that stage, there’s an audience, which is several televisions, and on each television a bust of a person appears. Then there’s a program that, when the viewer enters, the sensors warn them, the images change, and everyone starts applauding. It was really cool to do this work, because sometimes you come up with a big project, a complex installation, and you think: “Is this going to work?” It was really interesting to see the viewer come in and be taken aback, as if they were actually being applauded by the people present, though of course they knew that the people weren’t there. At the time, there wasn’t even this Zoom thing and so many videocalls. The Público installation inverts the place of the spectator and the artist. Usually, the public is there looking at the work and is protected, in a way, but when they enter this installation, everyone is looking, clapping, and the person becomes the center of attention. Of course, you know that they’re televisions and that it’s not live, but why does this cause discomfort, or embarrassment? When confronted with television screens, you end up wondering whether or not there really is someone there, even though you know there isn’t. But, for a second, you believe that there is. But for a second, you believe there is. For that second, you feel what you would feel if it were true. This puts us in conflict with the image and strains our relationship with it. That’s what interests me. I believe we have ancestral instincts that make us believe what we see. We are programmed to survive, to perceive a lion and know that we need to run away, and things like that. However, when you put a lion on the screen, life-size, you know that the lion isn’t there, but sometimes it seems that the mind doesn’t know. Hence so much manipulation and misunderstanding in today’s world of image propagation. My work plays with the perception of reality.

In general, I think your works have a very universal sensibility. There’s an economy to the settings, and even the clothes. It’s hard to identify where the photos were taken. Clearly, the body is female, and, over time, you realize it’s yours, but there’s a universality, even in the absence of text or words. Is this intentional or a consequence?

I hadn’t really thought about this idea of the universal, but rather an idea of the neutral, although I don’t think there is a neutral (laughs). I know that I don’t want to draw attention to the clothes I’m wearing, or to myself. I’m more interested when my face doesn’t show, although it’s hard to achieve that. I’m interested in talking about the body in general, a woman’s body, logically speaking. I think that each element adds other layers and often confuses. I do have a desire to access the diverse and so I try to make things neutral. For example, the series of works I call “Corte” is done in two ways: some works are neutral, with a white background, where I’m wearing more casual clothes, without patterns. There are others that were photographed in my grandmother’s house in Petrópolis, in an environment with patterned curtains and antique furniture, in which I’m wearing a black velvet skirt and a lace blouse. It’s a very old house that I know a lot about and which holds a lot of information. As a result, the photos also talk about tradition, family, a culture, women and rules and, in short, I think that environment brings it all together, so I decided to shoot there because I’m very interested in this aesthetic and its symbols. But it’s the only work I have like this. It’s something I’ve done very specifically. It has to do with me, with my history. In general, I strive for neutrality, because then I can talk about the cut, the body, movement, and very basic, though at the same time very important, things that deal with almost everyone’s life experience. I’m not just talking about myself. If I put on a taffeta dress, for example, I completely change the meaning of what is most basic. I think that each element that makes up the work can have a big impact, like music, for example. Almost none of my videos have music or soundtracks. I usually use the sound of the environment, of what’s happening right now. I think this also ties in with the fact that I don’t look for an interpretation. I don’t try to interpret because it has nothing to do with what I want to say. I try to carry out an action in order to make the idea work. It becomes more to the point. If I take a video of mine and add a sound, or a soundtrack, it needs to be something that makes sense in that context. In the rail work, I use these casual clothes and talk about the interaction of the image with the movement of the screen. Speaking of movement and perception, it doesn’t make sense to me to have clothes that symbolize a third thing, although jeans also symbolize something (laughs).

I see several of your works presenting a rupture, and all this economy of information, this neutrality, really emphasizes this rupture, which is sometimes aggressive, as in Fire, but also a rupture of movement, as in Movement². Here, we seek a rupture between the expectation of that inert image on the screen and the movement it provokes in space. Can you talk a bit more about this rupture in your work? Do you consider it an important aspect?

Yes, I think about and have done a bit of research into the term “iconoclasm”, which is this idea of destroying images so as not to leave a trace. However, the quest to destroy the image has always generated new images. For example, when the Catholics arrived in the Americas, they sought to destroy everything that symbolized original religions and culture in order to reduce their power. However, the result was the creation of syncretism, hybrid images, cultural mixtures and so on. I think that’s what my work is about: destroying in order to create something new. I have something very radical about destruction and a certain violent impulse. In the “Corte” and “Fogo” series, and in the “Derrube” video, this is very present. “Derrube” is an older work in which I break down a wall on which my image is projected. In this way, my image ends up disappearing. These works speak of violence, of rupture, in the sense of doing away with that appearance they propose destroying, cutting, burning my own image. But they also talk about questioning what is visible and creating something new, making room for other images and other realities.

Yes, your work deals a lot with this expectation of the gaze, dealing with what the eye sees and the expectation we have of the image we’re confronting.

It’s an overlap of things. It mixes a biological reaction that makes us see things in a certain, more intuitive way, with the social, cultural, and political context into which each person is inserted, which also defines our perception and/or allows us to question it.

Interview made on 21 November 2023 remotely via Zoom

Cut-out photography I 35×26 cm

2018

Cut-out photography | 135 x 95 cm

2019

Burnt photographs | 30 x 20 cm (each)

2020

2010/14

Views of the video installation – SESC Sorocaba, São Paulo

2017

Video installation

2009